Physicists create compressible optical quantum gas

Researchers at the University of Bonn have created a gas of light particles that can be extremely compressed. Their results confirm the predictions of central theories of quantum physics. The findings could also point the way to new types of sensors that can measure minute forces. The study is published in the journal Science.

Researchers at the University of Bonn have created a gas of light particles that can be extremely compressed. Their results confirm the predictions of central theories of quantum physics. The findings could also point the way to new types of sensors that can measure minute forces. The study is published in the journal Science.

If you plug the outlet of an air pump with your finger, you can still push its piston down. The reason: Gases are fairly easy to compress—unlike liquids, for example. If the pump contained water instead of air, it would be essentially impossible to move the piston, even with the greatest effort.

Gases usually consist of atoms or molecules that swirl more or less quickly through space. It is quite similar to light: Its smallest building blocks are photons, which in some respect behave like particles. And these photons can also be treated as gas, however, one that behaves somewhat unusually: You can compress it under certain conditions with almost no effort. At least that is what theory predicts.

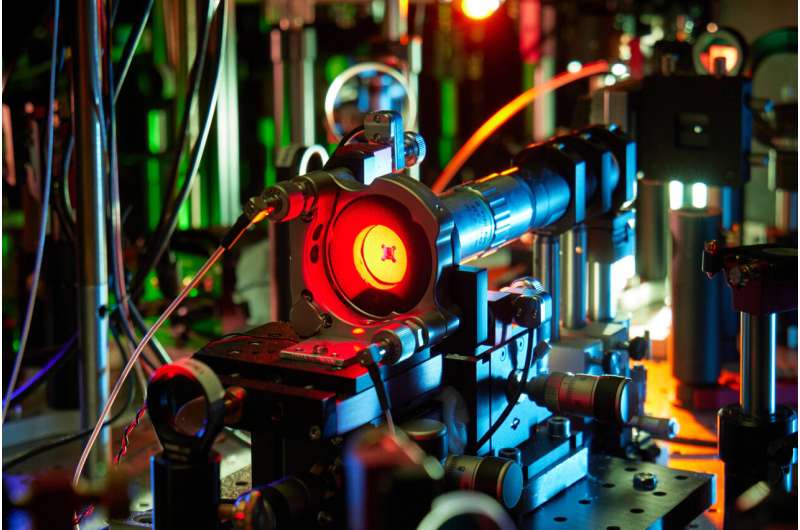

Photons in the mirror box

Researchers from the Institute of Applied Physics (IAP) at the University of Bonn have now demonstrated this very effect in experiments for the first time. "To do this, we stored light particles in a tiny box made of mirrors," explains Dr. Julian Schmitt of the IAP, who is a principal investigator in the group of Prof. Dr. Martin Weitz. "The more photons we put in there, the denser the photon gas became."

The rule is usually as follows: The denser a gas, the harder it is to compress. This is also the case with the plugged air pump—at first, the piston can be pushed down very easily, but at some point, it can hardly be moved any further, even when applying a lot of force. The Bonn experiments were initially similar: The more photons they put into the mirror box, the more difficult it became to compress the gas.

However, the behavior changed abruptly at a certain point: As soon as the photon gas exceeded a specific density, it could suddenly be compressed with almost no resistance. "This effect results from the rules of quantum mechanics," explains Schmitt, who is also an associate member of the Cluster of Excellence "Matter and Light for Quantum Computing" and project leader in the Transregio Collaborative Research Center 185. The reason: The light particles exhibit a "fuzziness"—in simple terms, their location is somewhat blurred. As they come very close to each other at high densities, the photons begin to overlap. Physicists then also speak of a "quantum degeneracy" of the gas. And it becomes much easier to compress such a quantum degenerate gas.

Self-organized photons

If the overlap is strong enough, the light particles fuse to form a kind of super-photon, a Bose-Einstein condensate. In very simplified terms, this process can be compared to the freezing of water: In a liquid state, the water molecules are disordered; then, at the freezing point, the first ice crystals form, which eventually merges into an extended, highly ordered ice layer. "Islands of order" are also formed just before the formation of the Bose-Einstein condensate, and they become larger and larger with the further addition of photons.

The condensate is formed only when these islands have grown so much that the order extends over the entire mirror box containing the photons. This can be compared to a lake on which independent ice floes have finally joined together to form a uniform surface. Naturally, this requires a much larger number of light particles in an extended box as compared to a small one. "We were able to demonstrate this relationship in our experiments," Schmitt points out.

To create a gas with variable particle numbers and well-defined temperatures, the researchers use a "heat bath": "We insert molecules into the mirror box that can absorb the photons," Schmitt explains. "Subsequently, they emit new photons that on average possess the temperature of the molecules—in our case, just under 300 Kelvin, which is about room temperature."

The researchers also had to overcome another obstacle: Photon gases are usually not uniformly dense—there are far more particles in some places than in others. This is due to the shape of the trap in which they are usually contained. "We took a different approach in our experiments," says Erik Bisley, first author of the publication. "We capture the photons in a flat-bottom mirror box that we created using a microstructuring method. This enabled us to create a homogeneous quantum gas of photons for the first time."

In the future, the quantum-enhanced compressibility of the gas will enable research into novel sensors that could measure tiny forces. Besides technological prospects, the results are also of great interest for fundamental research.

What's Your Reaction?